The question of freedom is often looked upon through the lens of un-freedom, defining the term not in terms of the positive but that of the negative, of what its lack implies. But there is an alternative approach to the question, framing freedom as being given the space — the nothingness — to thrive, evolve and grow. To let some-one or some-thing free is to let it go, to create an emptiness around them that they can choose to fill howsoever they wish, taking away the guardrail of concrete that chafes and injures the very thing it claims to protect. Ironically, it is the desire to protect and do good that is the source of all un-freedom. It is weakness that props up the proponents of un-freedom, whether it be a cry of help to save oneself or save the children or save the wretched. Morality is the fount of un-freedom, inviting the sludge that ossifies the spaces around us, driven relentlessly by judgment that hearkens to the call, coming for one and all of us. Conversely, a moral vacuum is the friend of freedom. To suspend judgment, to invite evil into the world without allowing it to consume the world and convert it into its own image, to embrace the void — this is what it means to cherish freedom. At every critical juncture, we must make this very choice: do we wish to play the game of morality and judgment, or do we ally ourselves with freedom?

“NO is a complete sentence.” —Anonymous

It’s surprising how much trouble people have with just saying ‘no’. It may well have something to do with social norms, but while I’ve never had any compunctions on this point, it wasn’t until recently that I realized how hard it is for people to simply say ‘no’ (to anything).

Being able to say ‘no’ is a superpower. The simplest way to do it might be to say “No” or “No, I won’t do that”, and then offer a long pause, at which point the other person will likely ask you why. If you’re feeling charitable, you might then take a deep breath and offer some explanation of why you won’t (note: won’t, not can’t). You don’t always have to offer an explanation, and you must never be apologetic about it unless you truly feel that way inside. Regardless, you’ve already won, because you’ve done the one thing that’ll give you peace of mind that compounds over time: you’ve established and communicated your boundaries, and put truth and kindness ahead of appearing nice.

In a previous post, I talked about false choices, situations where one is persuaded to pick from one of several sub-optimal options like A versus B when better ones exist outside the realm of consideration. I would like to highlight the other side of the problem, arguably a bigger deal for many people, which is this: it is usually not obvious how to classify a problem at hand into an A versus B situation in the first place.

Here’s an example: we have the well-known explore-exploit tradeoff that recognizes the dilemma we face between choosing the best option from what we know versus continuing to look for better options (at the cost of potentially losing what we already have in hand). In Algorithms to Live By, Brian Christian points out that the best approach for such a problem is to dedicate the first 37% of your time in explore mode and the rest in exploit mode, that is, picking the next available “best” option1. Here’s the kicker though: for someone who isn’t aware of this tradeoff in the first place and doesn’t realize that their actions could be classified into exploratory or exploitative ones, how are they to even know to look for a solution? And besides, it seems like we pulled this explore-exploit tradeoff out of thin air — what other dimensions are we missing?

Here are a few more:

| Category A | Category B |

|---|---|

| Explore | Exploit |

| Embracing Risk | Mitigating Risk |

| Effectiveness | Efficiency |

| Top-line Growth | Bottom-line Growth |

| Revenue | Profits |

There are undoubtedly many more that could be added to this list. I would offer the following observation: Category B is never enough — one must spend a good chunk of their time in Category A, maybe even up to 80% for some of them. I think it has something to do with how rapidly the environment is evolving, and how well-suited we are to adapt when our world shifts around us.

Reference this precise explanation of the optimal stopping problem and solution.

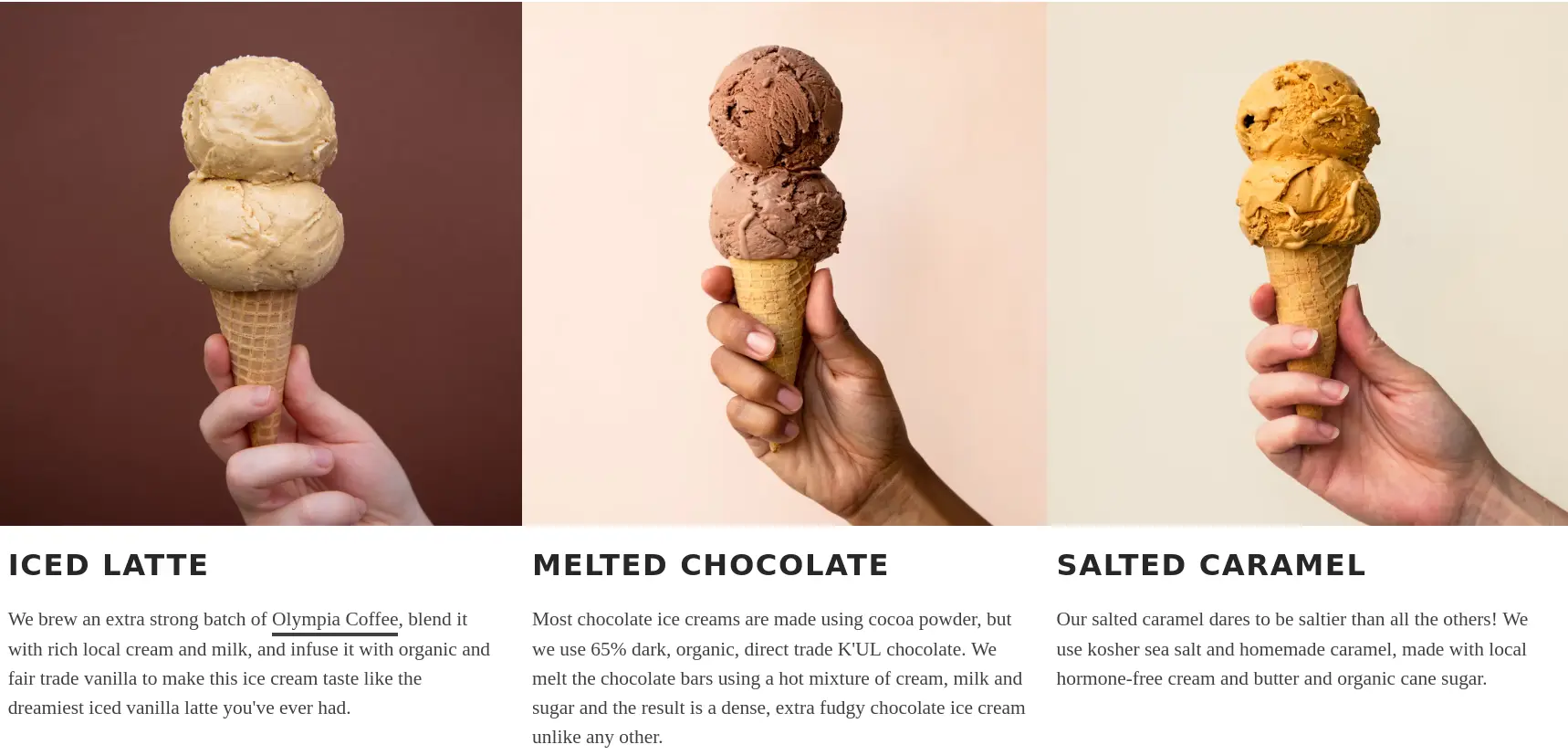

So much of our lives are affected by false choices. By ‘false choice’, I mean a decision where two options are presented to us and we make a choice without seeking out additional alternatives. Want Iced Latte or Melted Chocolate ice cream? Maybe the answer should be: Sea Salt & Caramel — but you have to know to ask!

Perhaps this is all a magic trick that we play upon on our own minds. It is my untested hypothesis that making the choices more detailed and intricate drives people to start focusing on its details and become less curious about alternatives — vanilla options, like Vanilla versus Chocolate, are more likely to be questioned than something exotic, like Iced Latte versus Melted Chocolate.

Within a group, the options being highly detailed can fool people into believing that they’ve been thought through deeply (by someone else). Some people have learned to invert the filter, and treat excess detail as a sign of shallow synthesis. The truth probably lies somewhere in between, and so this leads us to another type of false choice — options being considered mutually exclusive when they can very well co-exist, and implying a polarization when one really ought to speak of degrees within a spectrum.

Whenever I am presented with options, say A versus B, I usually start by seeking to understand how they came up with these options, and whether there were other options that got filtered out, based on unspoken assumptions or constraints. Then I check to see what they are optimizing for, and pick options that work, often going for a mix and match approach. The trick here is to never rule out options but simply put a pin in it saying, “This option works only if constraints X, Y and Z are broken…”

By the way, since you forgot to ask, the right answer to the ice cream conundrum is to have half Raspberry, half Chocolate, with some Candied Hazelnut as a topping.

Getting things done is a great way to keep moving forward in life with a sense of satisfaction. But sometimes, all one really needs is closure, and quitting is a perfectly good alternative.

I spent a good deal of time chipping away at creating a commenting system for this blog. The way it would work is that you would have a simple JavaScript-based submission form at the bottom of each post, and comment submissions (aka, replies) would traverse an AWS CloudFront Function for a clever spam check1 and an AWS Lambda Function for actual processing. Processing would result in the comment data (consisting of a simple name and reply enriched to create a child post that rendered beautifully below its parent) being sent to GitHub as a pull request, authenticated to my personal account that hosts the source code for this blog. I would then review and manually approve these pull requests as they came in (I didn’t expect much comment traffic anyway).

But I remained on the fence as to whether I even wanted to make this blog that interactive, and I never did get to a solution that motivated me to complete the work. And the work stayed in a limbo until two days ago, when I finally decided to abandon the idea altogether. And now a weight has been lifted off my shoulders….

The idea behind the clever spam check was to track a sequence of calls to CloudFront as the user navigated the site, and match this sequence against a state machine on the server side (using a key-value store available to CloudFront). For instance, a human would focus the text box and then type several characters — each of these ‘human-like’ events would generate calls to the server that drove the state machine. The state machine itself would remain hidden from view to the user, so while a bot could, in theory, replicate the call sequence, doing so would be a lot more challenging process to undertake.